A Very Technical Look at BitMessage: Learning From a Dead Project

At ByThere are a lot of cool projects that unfortunately have been abandoned or unmaintained for years, but that doesn’t mean they added no value. Studying what they’ve done, taking their unique ways of doing certain things and their problems can lead us to build something better. Bitmessage is one of those projects; it is an email-like service but fully peer-to-peer and decentralized, built upon the same principles. It used innovations of other projects like Bitcoin to build a new thing.

But sadly, Bitmessage didn’t seem to make it. Though it was a cool project, it never got independently audited and its latest release was in 2018. There aren’t many peers left on the network and its client has some known and critical vulnerabilities like remote code execution, but none of this means it served no good. There have been freedom-loving and privacy-caring people behind it, dedicating their time, money, and energy to build something valuable.

In this post, I wanted to take a technical look at this network, on how it worked in depth (like the post I did on Zeronet) in a very simple and easy-to-understand way.

What did Bitmessage do

Bitmessage was supposed to be like a truly P2P email system. You would send a message on the network, it would have been encrypted for the receiver and spread across the peers until the receiver got it. Everyone would get the message, but only the receiver would open it. That causes some issues, though. We’re relying too much on the encryption scheme and its implementation. If a flaw in the scheme was found, the whole network would become insecure until a new version was released, and then it would break compatibility with older versions. Here, a bad actor could log all messages flowing on the network and wait for the day that a vulnerability in encryption was found, then they would open all messages. Networks like Jami and Tox do this differently; they find the receiver and then directly communicate with them, which fixes that problem.

Mailing Lists

One of the interesting features of Bitmessage was its mailing list feature, which is a broadcast address that, when someone sends a message to it, a copy of the message gets sent to everyone in the subscription list of this address.

But the downside is that everyone can send a message to a mailing list in Bitmessage without even being a member of it, and that is the recipe for spam.

Subscriptions

Subscriptions in Bitmessage allow users to receive encrypted broadcasts from a subscribed address. The way that this encryption happens is not very secure. A broadcast message is encrypted with a key, which can be derived from the sender’s address. Once a broadcast is decrypted, the sender’s address is known, and after that, every broadcast ever sent and every broadcast that will be sent in the future can be decrypted.

Private Messages

Private messages in Bitmessage are those messages that have only one recipient. All private messages are encrypted using the receiver’s public key (and the receiver’s public key is the receiver’s address), and when the receiver successfully decrypts the sender’s message, they send an ACK message telling the sender that the message has been successfully received and decrypted. If the ACK message isn’t received within 2.5 days, the message expires and the sender will have to do the Proof-of-Work again.

BitMessage’s Encryption

Bitmessage used an ECIES (Elliptic Curve Integrated Encryption Scheme) to encrypt the payloads of the messages and broadcast objects.

This scheme uses ECDH (Elliptic Curve Diffie-Hellman) to generate a shared secret, which is then used to encrypt the data using AES-256 (Advanced Encryption Standard) in CBC mode.

This scheme, by today’s standards, isn’t that secure. The CBC mode adds a lot of complications and insecurities because it doesn’t have authentication of messages, and self-implementation of them leaves room for many errors and mistakes. A better scheme by today’s standards would use X25519 to exchange the keys and generate the shared secrets. X25519 is based on Curve25519, which is faster and more secure than ECDH.

Also, there are other new methods for exchanging keys besides elliptic curves and RSA, like Key Encapsulation Mechanisms (KEMs), which are supposed to reduce the complexity of the key exchange methods.

The encryption process in Bitmessage is as follows (taken from Bitmessage’s wiki):

- The destination public key is called K.

- Generate 16 random bytes using a secure random number generator. Call them IV.

- Generate a new random EC key pair with the private key called r and the public key called R.

- Do an EC point multiply with public key K and private key r. This gives you public key P.

- Use the X component of public key P and calculate the SHA512 hash H.

- The first 32 bytes of H are called key_e and the last 32 bytes are called key_m.

- Pad the input text to a multiple of 16 bytes, in accordance with PKCS7.

- Encrypt the data with AES-256-CBC, using IV as the initialization vector, key_e as the encryption key, and the padded input text as the payload. Call the output ciphertext.

- Calculate a 32-byte MAC with HMAC-SHA256, using key_m as salt and IV + R + ciphertext as data. Call the output MAC.

The resulting data is: IV + R + ciphertext + MAC

This could be improved in many ways, for example:

- Using a safe KDF like HKDF to derive the keys instead of using a hash like SHA512.

- Using an AEAD to ensure the integrity of the encrypted message instead of calculating the MAC separately and increasing the risk of implementation errors.

- Using a KEM to exchange the keys would simplify the exchange process while increasing security by reducing the risk of key interception or leakage.

Plausible Deniability

Plausible deniability is when someone can say they didn’t know about something bad that happened, and there is no clear proof to show they did.

Plausible deniability is a big part of Bitmessage. In Bitmessage, the messages are not only encrypted but also signed with the sender’s address to prevent strangers from claiming to be a specific person. However, this also causes problems: if a message is decrypted and the signature is verified, the content of the message can be used against the sender. But these actions can be taken for plausible deniability in Bitmessage:

- Deleting: Address blocks can be deleted from keys.dat so they are no longer used to send or receive messages.

- Publication: Another thing that can be done is to publicly share the address block in a crowded mailing list. This way, users can pretend that they never used that address at all, and there will be no proof that they actually did, or someone else who had access to that address block. But this comes with some consequences:

- Everyone can claim that they’re the true owner of the address, impersonating the address.

- Every message that was sent using or to the public address can be decrypted by everyone. While the messages delete after 2.5 days, there might always be a backup copy of the messages.

BitMessage’s Proof of Work

To prevent or at least reduce the spam on the network, Bitmessage used proof of work to address this problem.

Proof of work is a costly task for a computer to perform, for example, a calculation that requires time and effort (for a computer) to do, and it is verifiable by other people that this calculation or work is done correctly and there is no cheating involved.

Bitmessage uses a double round of SHA-512 for its proof of work, meaning it hashes a message twice with SHA-512. It is not very costly by modern standards, and in my opinion, it doesn’t prevent spam that much. It could have been improved by using a hash algorithm that requires memory to perform the hashing, usually a key derivation function (KDF) like Argon2id or scrypt. These algorithms not only require CPU/GPU power but also take up RAM, and RAM is much more expensive than CPU power.

hello

9b71d224bd62f3785d96d46ad3ea3d73319bfbc2890caadae2dff72519673ca72323c3d99ba5c11d7c7acc6e14b8c5da0c4663475c2e5c3adef46f73bcdec043 (first round of SHA-512)

0592a10584ffabf96539f3d780d776828c67da1ab5b169e9e8aed838aaecc9ed36d49ff1423c55f019e050c66c6324f53588be88894fef4dcffdb74b98e2b200 (second round of SHA-512)

BitMessage’s Addresses

In Bitmessage, all addresses are Base58 encoded hashes of the public key. The hash algorithm for address generation is different from its PoW algorithm; for addresses, Bitmessage uses RIPEMD-160 instead.

For example, a Bitmessage address looks like this:

BM-BcbRqcFFSQUUmXFKsPJgVQPSiFA3Xash

All Bitmessage addresses start with the characters “BM-“ to indicate they are part of the protocol. This is a good idea because when a network applies such a separator in the addresses, it becomes easier to identify newer versions of addresses. For example, if in a new version of Bitmessage they wanted to use a different hash or public key algorithm, they could have changed the address prefix to BMV2-, indicating it is version 2 of the address. This would let users know if they need a newer client and would prevent sending messages from unsupported clients to newer versions.

BitMessage’s Protocol

BitMessage’s Message Encoding

BitMessage’s protocol uses a custom encoding system for its messages that are sent over the network. It consists of several parts:

1. Message Header

- Magic (4 bytes): Identifies the network. It helps the protocol to recognize the beginning of a message. Known magic values include

0xE9BEB4D9. - Command (12 bytes): ASCII string identifying the type of message. It’s padded with NULL bytes (

\x00) to ensure a length of 12 bytes. - Length (4 bytes): Specifies the length of the payload. It’s an unsigned 32-bit integer, meaning it can describe a payload up to

4,294,967,295bytes, though restrictions limit it to 1,600,003 bytes. - Checksum (4 bytes): First 4 bytes of the SHA-512 hash of the payload to ensure data integrity.

- Message Payload (variable): The actual data being transmitted, which could vary based on the message type.

2. Variable Length Integer (VarInt)

- 1 byte: For values less than

0xFD. - 3 bytes: Starts with

0xFDfollowed by auint16_tvalue. - 5 bytes: Starts with

0xFEfollowed by auint32_tvalue. - 9 bytes: Starts with

0xFFfollowed by auint64_tvalue.

3. Variable Length String

- Prefixed with a VarInt indicating the length of the string, followed by the string itself.

4. Variable Length List of Integers

- Starts with a VarInt specifying the number of integers, followed by the integers themselves, each encoded as VarInts.

5. Network Address Structure

- Time (8 bytes): Timestamp.

- Stream (4 bytes): Stream number for the node.

- Services (8 bytes): Node services bitfield.

- IPv6/4 (16 bytes): IPv6 address (or IPv4 mapped into IPv6).

- Port (2 bytes): Network port.

6. Inventory Vectors

- Used to announce or request objects within the network. Each entry includes a 32-byte hash representing the object.

7. Encrypted Payload

- IV (16 bytes): Initialization vector for AES-256-CBC encryption.

- Curve Type (2 bytes): Identifies the elliptic curve used (e.g., 0x02CA for secp256k1).

- Public Key Components (X and Y): Lengths and values of the X and Y coordinates of the elliptic curve public key.

- Ciphertext: The actual encrypted data.

- MAC (32 bytes): Message Authentication Code using HMAC-SHA256.

8. Unencrypted Message Data

- Various fields including version, address version, stream number, public keys, and a bitfield indicating node behavior.

- Nonce Trials per Byte and Extra Bytes: Difficulty settings for Proof of Work.

- RIPE Hash (20 bytes): Represents the receiver’s public key.

- Message Encoding: Specifies how the message is formatted (e.g., UTF-8).

- Signature: ECDSA signature covering specific parts of the message.

9. Message Types

- Version Message: Announces a node’s protocol version and capabilities.

- Verack Message: Acknowledges the reception of a version message.

- Addr Message: Provides information about known nodes.

- Inv and Getdata Messages: Handle the exchange of object information and requests.

- Object Message: Carries content that propagates across the network, such as public keys, messages, or broadcasts.

10. Pubkey and Broadcast Structures

- Pubkey: Contains public keys for signing and encryption, behavior bitfields, and optionally encrypted data (in version 4 and above).

- Broadcast: Used for sending messages to subscribers, with version 4 and 5 utilizing tags and encryption for additional security.

There could be some improvement to this encoding format. For example:

- The protocol uses a variable-length encoding that allows smaller numbers to be represented with fewer bytes. However, the current scheme (e.g., using 0xFD, 0xFE, and 0xFF prefixes) might be wasteful for certain number ranges. A more efficient variable-length encoding scheme, such as LEB128 (Little Endian Base 128), which is widely used in formats like WebAssembly, encodes integers using a variable number of bytes, with no need for extra prefix bytes, making it more space-efficient for both small and large numbers.

- The protocol stores full 128-bit IPv6 addresses, which can be wasteful, especially for addresses with long sequences of zeros. It could use address compression techniques, similar to how IPv6 addresses are represented textually (e.g., using

::to replace sequences of zeros). Alternatively, apply prefix compression if many addresses share a common prefix. - Commands are encoded as fixed-length, 12-byte ASCII strings, which is simple but inefficient and inflexible. Using a variable-length encoding for commands, storing the command length as a prefix, followed by the command string, would reduce the size of the message when the command is shorter than 12 bytes.

BitMessage’s Message Types

Message types refer to the different kinds of messages that nodes (computers) can send and receive in a peer-to-peer network. These messages are used for various purposes, including establishing connections, sharing information about nodes, requesting and receiving data, and managing the objects (like messages or keys) in the network.

1. Version

- What It Is: When two nodes first connect, they need to agree on the version of the protocol they are using.

- What It Contains:

- Version: Tells which version of the protocol the node is using (should be version 3).

- Services: Lists the features the node supports (like network connectivity or security options).

- Timestamp: The current time.

- Addresses: The network addresses of the node sending and receiving the message.

- Nonce: A random number used to check if the connection is with itself.

- User Agent: Information about the software being used.

- Stream Numbers: The streams of messages the node is interested in.

2. Verack

- What It Is: A simple acknowledgment message sent in reply to the

versionmessage. - What It Contains: Just a header with the command “verack” (short for “version acknowledgment”).

- Purpose: Signals that the connection setup is complete and both nodes are ready to communicate. After this, they can start a secure connection if both support SSL/TLS.

3. Addr

- What It Is: A message that provides information about other nodes in the network.

- What It Contains:

- Count: The number of addresses being shared.

- Address List: The addresses of other nodes.

4. Inv

- What It Is: A message used to announce that a node knows about certain objects (like messages or public keys).

- What It Contains:

- Count: The number of objects being announced.

- Inventory: Details of each object.

5. Getdata

- What It Is: A request to get the actual data of specific objects after they have been announced by

inv. - What It Contains:

- Count: The number of objects being requested.

- Inventory: Details of each object requested.

6. Object

- What It Is: This is the actual data message that gets shared across the network. It’s the primary way to send information.

- What It Contains:

- Nonce: A random number used to ensure the message has been properly processed.

- Expires Time: When the object will no longer be valid.

- Object Type: Tells what kind of message it is (like a request for a public key, a public key, a message, or a broadcast).

- Version: The version of the object format.

- Stream Number: The stream the object is related to.

- Object Payload: The actual content of the message, which varies depending on the type of object.

The message types could have been improved by implementing these methods:

- A more detailed protocol negotiation mechanism to handle different versions and backward compatibility better.

- Including additional metadata about the node’s capabilities or preferences (e.g., supported encryption algorithms or message types) to optimize the interactions.

- Ensuring SSL/TLS handshakes are mandatory and verified before proceeding with further messages.

- Implementing mechanisms to dynamically update and validate node addresses to ensure that outdated or invalid addresses are removed from the list.

- Using methods to anonymize node addresses or using temporary addresses that change periodically to increase privacy.

- Supporting batch requests to retrieve multiple objects in a single

getdatamessage, reducing overhead and improving efficiency. - Implementing priority mechanisms to request the most critical data first and supporting caching to avoid redundant requests for the same data.

- Using compression algorithms to reduce the size of

object

messages, especially for large payloads.

- Implementing version control within

objectmessages to handle changes in the object structure or content format over time.

BitMessage’s Object Types

Object types are specific data structures used to perform various operations within the network. Each object type serves a particular purpose, such as requesting a public key, sending messages, broadcasting information to multiple recipients, or transmitting a public key. These objects are the building blocks of the protocol, enabling nodes (participants in the network) to communicate, authenticate, and exchange information securely and efficiently.

1. getpubkey Object

- Purpose: This object is used by a node to request a public key from another node when it has the hash of the public key (from an address) but not the key itself.

- Fields:

ripe(20 bytes): This is the RIPEMD-160 hash of the public key. It is included only when the address version is 3 or below.tag(32 bytes): This is derived from the address version, stream number, and ripe hash. It’s included when the address version is 4 or above, ensuring that the requesting node can correctly identify the public key.

2. pubkey Object

- Purpose: The

pubkeyobject contains the public key information used for cryptographic operations like signing and encryption. The format of this object evolves across different protocol versions. - Version 2:

behavior bitfield(4 bytes): Indicates the behaviors and features supported by the node. This is a set of flags that tell other nodes what to expect.public signing key(64 bytes): The ECC public key used for signing messages, provided in an uncompressed format.public encryption key(64 bytes): The ECC public key used for encrypting messages, also in an uncompressed format.

- Version 3: Builds upon version 2 by adding:

nonce_trials_per_byte(variable length): Defines how hard the Proof of Work (PoW) needs to be for messages accepted by the node. A higher value increases the difficulty.extra_bytes(variable length): Adds to the message length to increase the difficulty of sending small messages.sig_length(variable length): Length of the signature.signature(variable length): The ECDSA signature that covers the object header and data.

- Version 4: In version 4, most of the pubkey data is encrypted:

tag(32 bytes): Helps in identifying the correct pubkey for decryption.encrypted(variable length): Contains encrypted data, which includes fields like the behavior bitfield, public signing key, and public encryption key. This encryption is intended to prevent spam or abuse of the public key.

3. msg Object

- Purpose: The

msgobject is used for sending person-to-person messages within the network. - Fields:

encrypted(variable length): The message data is encrypted to ensure confidentiality. The details of this encryption are handled similarly to how pubkeys are encrypted, ensuring only the intended recipient can read the message.

4. broadcast Object

- Purpose: The

broadcastobject allows a user to send messages to all subscribers of an address. This is typically used for announcements or public messages. - Fields:

tag(32 bytes): Similar to thepubkeyobject, it helps identify the broadcast messages that are relevant to a particular address.encrypted(variable length): Contains the encrypted broadcast data. Like in themsgobject, the encryption ensures that only the intended recipients can decrypt and view the broadcast.

Encryption Mechanism

- For Version 4+ Objects:

- The encryption is done using a key derived from the double SHA-512 hash of the address version, stream number, and the ripe hash of the address. This ensures that only nodes that know the address can decrypt the pubkey or broadcast message, adding a layer of privacy and security.

- The process involves creating a public and private key pair from the first 32 bytes of the hash, which is then used for encrypting the pubkey data.

Understanding Specific Fields:

behavior bitfield: This is a bitmask that specifies what behaviors the node supports. Each bit in the 32-bit field might represent a different capability or feature.public signing keyandpublic encryption key: These are standard ECC (Elliptic Curve Cryptography) keys used in the cryptographic processes of signing messages to verify authenticity and encrypting messages to ensure privacy.nonce_trials_per_byteandextra_bytes: These are parameters related to the Proof of Work mechanism, which is used to prevent spam by making it computationally expensive to send messages.tag: This is a unique identifier derived from the address data, allowing nodes to quickly determine whether a particular piece of data is relevant to them.

Object types also have some issues that could have been addressed and improved:

- Instead of requesting public keys using a hash, using a more direct method to find and retrieve keys quickly.

- Allowing the

behavior bitfieldand other metadata to be dynamically updated rather than fixed, so nodes can negotiate features dynamically. - Implementing data compression to reduce the size of encrypted messages and improve transmission efficiency.

- Improving the tagging mechanism to handle larger and more complex broadcasts efficiently. For instance, using hierarchical tagging to manage different types of broadcasts.

BitMessage’s Files

BitMessage uses several .dat files to store crucial data for the client to work:

Knownnodes.dat

BitMessage uses a file named knownnodes.dat to store the IP addresses and ports of the nodes that run BitMessage. These nodes help bootstrap the connection to the network.

Keys.dat

keys.dat is a file used by BitMessage to store important settings and address information.

This file is the most important file in BitMessage as it contains all your keys; if you lose this file, you lose your BitMessage identity (which is your private/public keys).

Configuration Sections

-

[DEFAULT] and [bitmessagesettings]

-

[DEFAULT]: Contains basic settings like labels for unused addresses.

-

[bitmessagesettings]: Contains detailed configuration options for BitMessage, such as:

- Port numbers, time formats, and proxy settings.

- Whether to start the application on login or minimize it to the tray.

- API settings, which allow external applications to interact with BitMessage.

- Encryption settings for keys and messages.

Example:

[DEFAULT] label = unused address [bitmessagesettings] settingsversion = 5 port = 8444 timeformat = %%a, %%d %%b %%Y %%I:%%M %%p blackwhitelist = black startonlogon = False minimizetotray = True showtraynotifications = False startintray = False socksproxytype = none sockshostname = localhost socksport = 9050 socksauthentication = False socksusername = USER sockspassword = PASS keysencrypted = false messagesencrypted = false apienabled = true apiport = 8442 apiinterface = 127.0.0.1 apiusername = API-Username apipassword = API-Password defaultnoncetrialsperbyte = 320 defaultpayloadlengthextrabytes = 14000

-

-

Address Sections

-

Contains information about addresses you have created.

Example:

[DEFAULT] label = unused address [bitmessagesettings] settingsversion = 5 port = 8444 timeformat = %%a, %%d %%b %%Y %%I:%%M %%p blackwhitelist = black startonlogon = False minimizetotray = True showtraynotifications = False startintray = False socksproxytype = none sockshostname = localhost socksport = 9050 socksauthentication = False socksusername = USER sockspassword = PASS keysencrypted = false messagesencrypted = false apienabled = true apiport = 8442 apiinterface = 127.0.0.1 apiusername = API-Username apipassword = API-Password defaultnoncetrialsperbyte = 320 defaultpayloadlengthextrabytes = 14000By deleting the address block from

keys.dat, you’ll remove the address from the client.

-

messages.dat

All messages in BitMessage are stored in a SQLite database named messages.dat, along with keys.dat and knownnodes.dat in the same directory.

This database uses different tables for different messages, for example, messages that were retrieved and decrypted, sent messages, and also some app configurations:

inbox Table:

This table contains messages that were retrieved and were successfully decrypted. It also stores trash messages as well.

CREATE TABLE inbox (

msgid blob,

toaddress text,

fromaddress text,

subject text,

received text,

message text,

folder text,

encodingtype int,

read bool,

UNIQUE(msgid) ON CONFLICT REPLACE)

sent Table:

Similar to the inbox table, it contains only the sent messages, including the trashed sent messages:

CREATE TABLE sent (

msgid blob,

toaddress text,

toripe blob,

fromaddress text,

subject text,

message text,

ackdata blob,

lastactiontime integer,

status text,

pubkeyretrynumber integer,

msgretrynumber integer,

folder text,

encodingtype int

)

subscription Table:

This table contains all the addresses that the user has subscribed to:

CREATE TABLE subscriptions (

label text,

address text,

enabled bool

)

addressbook Table:

This table contains all of the addresses that a user has communicated with in the past, like a phonebook:

CREATE TABLE addressbook (

label text,

address text

)

blacklist Table:

As the name suggests, any address that a user blocks will be stored in this table to prevent future communications with these addresses:

CREATE TABLE blacklist (

label text,

address text,

enabled bool

)

whitelist Table:

This table, similar to the blacklist table, contains addresses that are whitelisted. If the field enabled is set to true, the user can only communicate with the addresses in this table.

CREATE TABLE whitelist (

label text,

address text,

enabled bool

)

knownnodes Table:

This table was created for future use and to replace the knownnodes.dat file, which never happened as the project’s development halted.

CREATE TABLE knownnodes (

timelastseen int,

stream int,

services blob,

host blob,

port blob,

UNIQUE(host, stream, port) ON CONFLICT REPLACE)

settings Table:

This table, like the knownnodes table, is not implemented and was set to replace the keys.dat file configurations.

CREATE TABLE settings (

key blob,

value blob,

UNIQUE(key) ON CONFLICT REPLACE)

pubkeys Table:

This table contains public keys created by the user and the time they were last transmitted.

CREATE TABLE pubkeys (

hash blob,

transmitdata blob,

time int,

usedpersonally text,

UNIQUE(hash) ON CONFLICT REPLACE)

This approach has some obvious flaws that could have been addressed relatively easily:

- There is no need for storing sent and retrieved messages in separate tables; it could have been done by adding a field to a table called

messagesto determine whether it is sent or received. This would reduce a table in the database, making it smaller, especially as it is a file-based database. - Whitelists and blacklists could have been implemented into the

addressbooktable by adding a field to determine whether the address is whitelisted or blacklisted. - Using a file-based database for storing messages is not a good idea as they will get huge and will slow down as they grow more and more with usage.

- Configurations such as

knownnodesaren’t related to the messages and should have a separate database, perhaps namedconfigs.dat, to store all configurations and settings.

BitMessage’s Stream

In BitMessage, a stream is like a separate channel or group where nodes can communicate. Streams in BitMessage help organize and manage communication between nodes. They allow for more efficient data handling and keep the network organized.

This feature was never fully implemented to have multiple streams, and all addresses use stream 1 in BitMessage. When you create a new address, you usually set it up with a stream number, which is stream 1.

Stream 1 is the main or “master” stream. It’s the primary stream and, at the moment, the only one.

If you have addresses in different streams, your BitMessage client will connect to other clients in those specific streams only. This helps manage and reduce the amount of data your client handles. Your client will also connect to streams of addresses you are subscribed to.

Clients occasionally connect to Stream 1 to let other clients know that they exist. This helps clients find out which stream a particular address is using.

If there are too many messages in a stream, clients can create new streams (child streams) to manage the load. This helps keep the traffic and messages more manageable.

When someone wants to send you a private message, they need to find your stream and send it there. You then need to connect back to their stream to acknowledge receipt of the message.

Broadcasts are sent to the stream associated with the sending address. If you want to receive broadcasts from another stream, you have to connect to that stream and check for messages manually. For example, if you’re in Stream 5 and want updates from Stream 1, you need to connect to Stream 1 to get those updates.

This feature, if implemented fully, could benefit a searching system where users could look up different stream numbers and connect to those. It could also allow users to prioritize streams based on their preferences. This way, important streams receive more attention and resources, while less critical ones are managed with lower priority.

Good BitMessage’s Proposals

BitMessage had some good proposals to implement. If development had continued, it could have made a solid network.

Scalability through Prefix Filtering

This proposal was to make BitMessage more scalable. The proposal is still a work in progress, and some details are yet to be finalized. It suggests a new system to handle how messages are routed through the network to manage increasing traffic efficiently.

In this proposal, every BitMessage address and network node will have a ‘prefix’ and a ‘prefix length.’ These determine how messages are routed and how much traffic each node handles.

Nodes will be grouped into overlapping ‘streams’ based on these prefixes. As the network grows or shrinks, both addresses and nodes will move between streams to balance traffic and privacy.

Each message or object has a ‘prefix nonce’ that determines which streams it will travel through. Objects are processed in their stream and all higher streams in the same branch.

Stream Structure

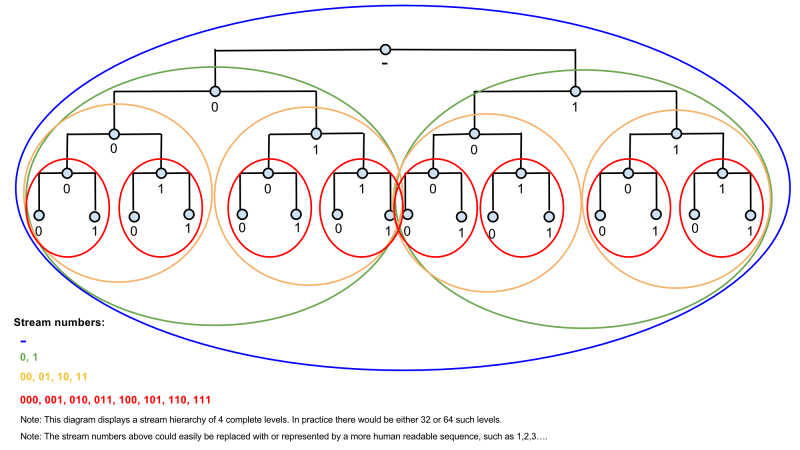

The diagram below shows the proposed structure of streams in BitMessage:

In the diagram above, the small, light blue circles represent groups of nodes, and the large colored circles represent streams.

Node Connections

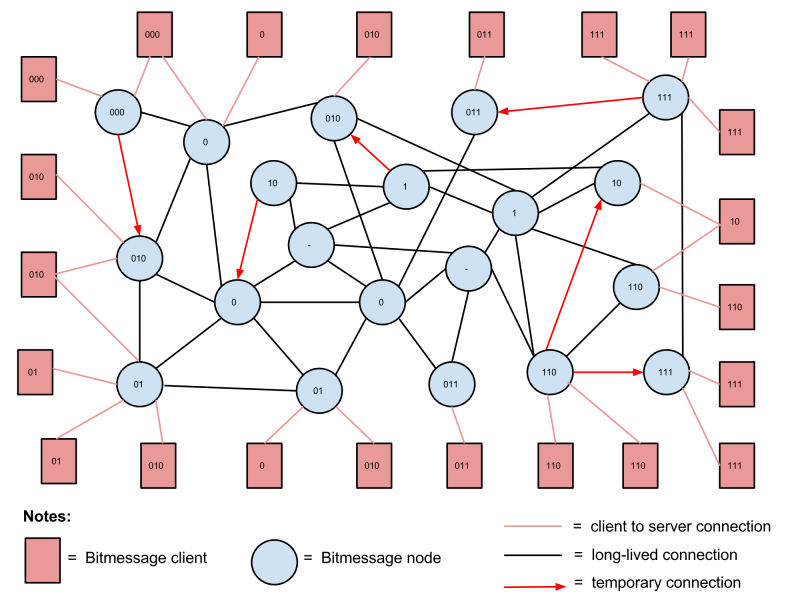

The diagram below shows the connections between nodes and clients under the proposed system:

Nodes and clients are labeled with a stream number, which corresponds to the stream numbers in the stream structure diagram above.

Proposed Changes

- Prefixes:

- Purpose: Prefixes route messages through the network. Instead of creating or deleting streams, this proposal uses a vast number of possible prefix values to manage traffic and privacy.

- Node and Address Management: Nodes and addresses are assigned a prefix and prefix length to control their traffic handling and balance anonymity with efficiency.

- Address and Object Structure:

- Address Prefix: The prefix is part of the address and does not change.

- Prefix Length: Determines the address’s stream. Changing the prefix length adjusts the stream assignment.

- Object Structure: Messages (objects) include a ‘prefix nonce’ to dictate their propagation path.

- Stream Hierarchy:

- The proposed system involves a multi-level hierarchy of streams. Each stream level handles different traffic volumes and maintains connections accordingly.

How Objects Travel and Nodes Connect

- Node Connections:

- Nodes connect to multiple nodes in their stream and nearby streams. They also connect directly to other streams as needed.

- Higher-capacity nodes maintain more connections.

- Message Propagation:

- Nodes process messages in their stream and all higher streams within the same branch.

Client Procedures

- Creating an Address:

- The client requests information on current traffic levels, sets a prefix length for the address, and generates a pubkey with this prefix length.

- The client then sends the pubkey to the appropriate nodes based on the stream.

- Retrieving a Pubkey:

- The client queries nodes in the stream to get the pubkey for an address, matching the address’s prefix value.

- Sending a Message:

- The client sets the prefix nonce of the message to match the destination address’s prefix and sends it to the relevant stream.

- Retrieving Messages:

- The client connects to nodes in the address’s stream or higher streams to request and process messages.

- Broadcasts:

- Broadcasts are sent to all nodes in the destination address’s stream. Clients need to periodically check these streams for new broadcasts from subscribed addresses.

Argothas Architecture

The goal of this proposal is to make it more scalable and user-friendly while preserving privacy. It is worth mentioning that this system sacrifices some aspects of complete anonymity and the ability to check for new messages instantly.

The new system involves several types of servers:

- Data Server (DS): Stores actual messages.

- Introduction Server (IS): Handles notification messages that inform users about new messages.

- Directory Server (DIR): Keeps track of all available servers so clients can find them.

New Address Process

- Create Address: The user creates a new BitMessage address.

- Find Servers: The user connects to a DIR to get a list of available ISs.

- Select ISs: The user chooses some ISs to use.

- Request Access: The user contacts the chosen ISs to request access.

- Store Details: If accepted, the IS’s details are stored with the user’s address.

Why Multiple ISs?

- Redundancy: If one IS is down, the user can still receive messages through others.

- Privacy: Using multiple ISs prevents any single IS from seeing all messages.

New Message Process

- Create Message: The sender prepares the message.

- Choose DS: The sender picks a Data Server to store the message.

- Store Message: The DS responds with a minimum proof-of-work value (security measure).

- Send Message: The sender uploads the message to the DS.

- Prepare Notification: The sender creates a notification message (NMESSAGE) with instructions for the recipient.

- Send Notification: The sender sends the NMESSAGE to the chosen ISs.

Receiving Messages

- Check ISs: The recipient periodically connects to their ISs to check for new notifications.

- Retrieve Messages: The recipient decrypts the notification and then fetches the actual messages from the Data Servers.

Onion Routing

- Purpose: Onion routing (like TOR) hides users’ IP addresses to prevent tracking and linking of messages.

- Question: Should BitMessage clients use TOR, or should the BitMessage network create its own onion routing system?

This proposal suggests a more scalable and private architecture for BitMessage. It involves using multiple servers to handle different types of data, distributing trust among them, and incorporating onion routing for enhanced privacy.

Bitmessage was a great project aiming to create a fully decentralized and private messaging system. Even though it’s no longer maintained and has some serious issues, it was an appreciable effort in its time.

By studying Bitmessage and other similar projects, we can learn valuable lessons from their innovations and challenges. These lessons help us understand what worked, what didn’t, and how we can build even better systems in the future.

The dedication of the people behind Bitmessage, who worked hard to create something meaningful, is a testament to their commitment to privacy and freedom. Their work, despite its limitations, has paved the way for new ideas and improvements in the world of decentralized communication.

While Bitmessage may be a project of the past, its impact continues to guide future developments in privacy-focused and decentralized technologies.

As always, this post is freely available on my GitHub. If you see any problems or have any suggestions, please make a pull request or open an issue.