Hacking a CTF: Do not use ECB mode for encryption

At ByI recently started doing CTF challenges. A few days ago, I was working on a challenge from 247CTF.com. I found a challenge that, in my opinion, shows why using ECB(Electronic Codebook) mode for encrypting with block ciphers like AES or Twofish isn’t a good idea. So, I decided to write a series of blog posts where I solve these challenges and explain how to prevent these kinds of attacks.

The challenge was quite simple. It was a website with two parts: /encrypt and /get_flag. Both parts needed a hex-encoded message called user.

Understanding the Source Code

This challenge provided the source code for us, making it quite easy to reverse engineer and understand how it works:

from Crypto.Cipher import AES

from flask import Flask, request

from secret import flag, aes_key, secret_key

app = Flask(__name__)

app.config['SECRET_KEY'] = secret_key

app.config['DEBUG'] = False

flag_user = 'impossible_flag_user'

class AESCipher():

def __init__(self):

self.key = aes_key

self.cipher = AES.new(self.key, AES.MODE_ECB)

self.pad = lambda s: s + (AES.block_size - len(s) % AES.block_size) * chr(AES.block_size - len(s) % AES.block_size)

self.unpad = lambda s: s[:-ord(s[len(s) - 1:])]

def encrypt(self, plaintext):

return self.cipher.encrypt(self.pad(plaintext)).encode('hex')

def decrypt(self, encrypted):

return self.unpad(self.cipher.decrypt(encrypted.decode('hex')))

@app.route("/")

def main():

return "

%s

" % open(__file__).read()

@app.route("/encrypt")

def encrypt():

try:

user = request.args.get('user').decode('hex')

if user == flag_user:

return 'No cheating!'

return AESCipher().encrypt(user)

except:

return 'Something went wrong!'

@app.route("/get_flag")

def get_flag():

try:

if AESCipher().decrypt(request.args.get('user')) == flag_user:

return flag

else:

return 'Invalid user!'

except:

return 'Something went wrong!'

if __name__ == "__main__":

app.run()

Just by looking at the code, it’s obvious that we need to encrypt the impossible_flag_user using the AESCipher class defined in the code. The class employs a straightforward algorithm for padding and utilizes AES with ECB mode for encryption. The secret key is imported from another Python file, which we don’t have access to. This means we can’t simply rewrite the AESCipher class and encrypt whatever we want.

On the other hand, the /encrypt route takes a hex-encoded payload named user and decodes it. If the decoded value is equal to impossible_flag_user, it returns a ‘No cheating!’ message. However, to obtain the flag, we need to provide the /get_flag route with a hex-encoded payload named user that, when decrypted, equals impossible_flag_user.

@app.route("/encrypt")

def encrypt():

try:

user = request.args.get('user').decode('hex')

if user == flag_user:

return 'No cheating!'

return AESCipher().encrypt(user)

except:

return 'Something went wrong!'

So, what we can do is attack the implementation of the encryption scheme, which is the AESCipher class. The two main issues that come to mind when looking at it are the self-rolled padding algorithm and the use of ECB mode.

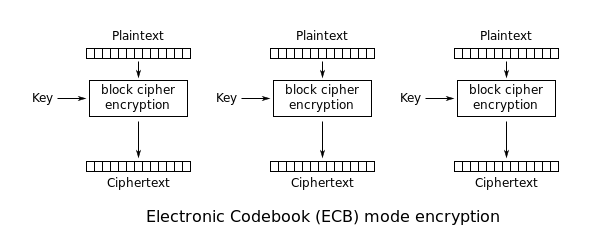

But what is ECB mode and how can it help us bypass that restriction? Well, ECB mode is the simplest way of encrypting blocks in block cipher algorithms. It works by breaking down the plaintext data into blocks of a fixed size and encrypting each block with the key. This process is repeated for each chunk until it reaches the last block. The final block is then padded to match the block size of the block cipher, and all the blocks are arranged in series to form the ciphertext:

But what’s the problem? ECB mode lacks diffusion, meaning it doesn’t obscure the correlation between the plaintext and the ciphertext. This weakness is what we will leverage to our advantage when encrypting the impossible_flag_user with it.

Performing the Attack

The first thing that came to my mind was that I could encrypt the impossible_flag_user partially to obtain some encrypted segments. To achieve this, I replaced the user in the plaintext with 0000 to maintain the same length. Here are the results:

939454b054b7379b0709a270b894025c1c3b822d1217b7af1516eccddb9349fc

Next, I encrypted only the user and obtained the following result:

707ece4f0913868ec5df07d131b0822d

Now, all I had to do was replace one block size length (16 bytes in this case) from the first encrypted plaintext with the corresponding portion from the second encrypted plaintext:

939454b054b7379b0709a270b894025c707ece4f0913868ec5df07d131b0822d

Now, by sending this modified ciphertext to the /get_flag route, we obtain the flag:

247CTF{ddd01e396dc1965c3fcf943f3968aa39}

The reason this happened is that the user was our last chunk, and because there was no random initializing vector, no matter how many times we encrypt that last chunk, we’d get the same result. Essentially, we encrypted the initial chunks and then appended the last chunk to bypass the restriction and obtain the flag.

This attack could have been easily prevented by using a cipher mode that provides diffusion and authentication, such as GCM_SIV. This mode eliminates the need for padding, and the ciphertext can be authenticated later.

This blog is available on my GitHub, and if you find the content interesting, you can give it a star or consider making a donation here.